At times scary, often silly, and depicted in exquisitely-minute detail, demons of Japanese folklore imagined and drawn by Japan's first political caricaturist, the voraciously talented Kawanabe Kyōsai.

Brutal change creates a chasm in society. A wedge-like space between the thing being discarded and the new thing not yet formed. From that chasm springs uncertainty, doubt, despair, agitation, excitement, hope, etc. This state is a shocker for most of us: we adopt a 'keep calm and carry on' sentiment, muted actions no greater than shaking a fist at morning headlines. Some humans do more (where would we be without Martin Luther King, Jr.'s permanent protest?).

Although it might feel that we are in a brutal period of change now more than ever, there were periods in time that were far more destabilizing, such as war (from which came Eliot's culmination poem: "The Waste Land") or plagues (produced a new literary form, a journalistic/literary hybrid of Daniel Defoe). And let's not forget technological advancement. Less brutal than war but no less divisive, periods of modernization produce camps of individuals who steadfastly grip the way we were; and those who rush into the future precociously.

Artists, those who write the past and sketch the future, are in the middle. The late 19th century in Japan was such a time to be an artist.

Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (May 18, 1831 – April 26, 1889) practiced traditional Japanese painting in the style of the artist Hokusai and represented traditional subjects in his makimono "scroll" work. At the same time, Kyōsai was a forward-thinking, irreverent troublemaker, repeatedly arrested by the authorities and one of Japan's first political caricaturists who made significant contributions to the 'manga' genre of Japanese cartoons.

I am naturally partial to his crow pictures. In Japanese folklore, crows represent a spirit (Karasu tengu) that would steal children and hide them in the mountains. In the West, crows present something ominous, a shadowy self.

"Crow Resting on Wood Trunk" by Kawanabe Kyōsai. Learn more.

"Crow Resting on Wood Trunk" by Kawanabe Kyōsai. Learn more.Kyōsai was the son of a Samurai, Japan's dignified and educated ruling class. He came of age in the Meiji Period, a time of extremely rapid change: Japan shifted from a land-based feudal governance system to an industrialized nation-state. Political reality fell behind people's aspirations of what could be, and in many cases, what had been promised in the original Meiji Proclamation of 1868.

Artists and illustrators like Kyōsai met this uncertainty with enormous creative output. His painted crows notwithstanding, it is Kyōsai's grossly demonic and yet strangely comical book, Pictures of One Hundred Demons, published posthumously in 1890, for which the artist is most well-known.

"Adults and children huddle around a brazier, or coal fire, to hear ghost stories."

"Adults and children huddle around a brazier, or coal fire, to hear ghost stories."Like many cultures, Japan has an ancient - usually oral - tradition of inventing and perpetuating the existence of creatures called yōkai. These supernatural entities - sometimes evil, sometimes good - explain the inexplicable, like the yamabiko spirit that hollers back when one shouts into a mountain.

The yōkai are not necessarily demons, but they could be. More to the point, Kyōsai imagined, intellectually and visually, hundreds of monsters to create his book.

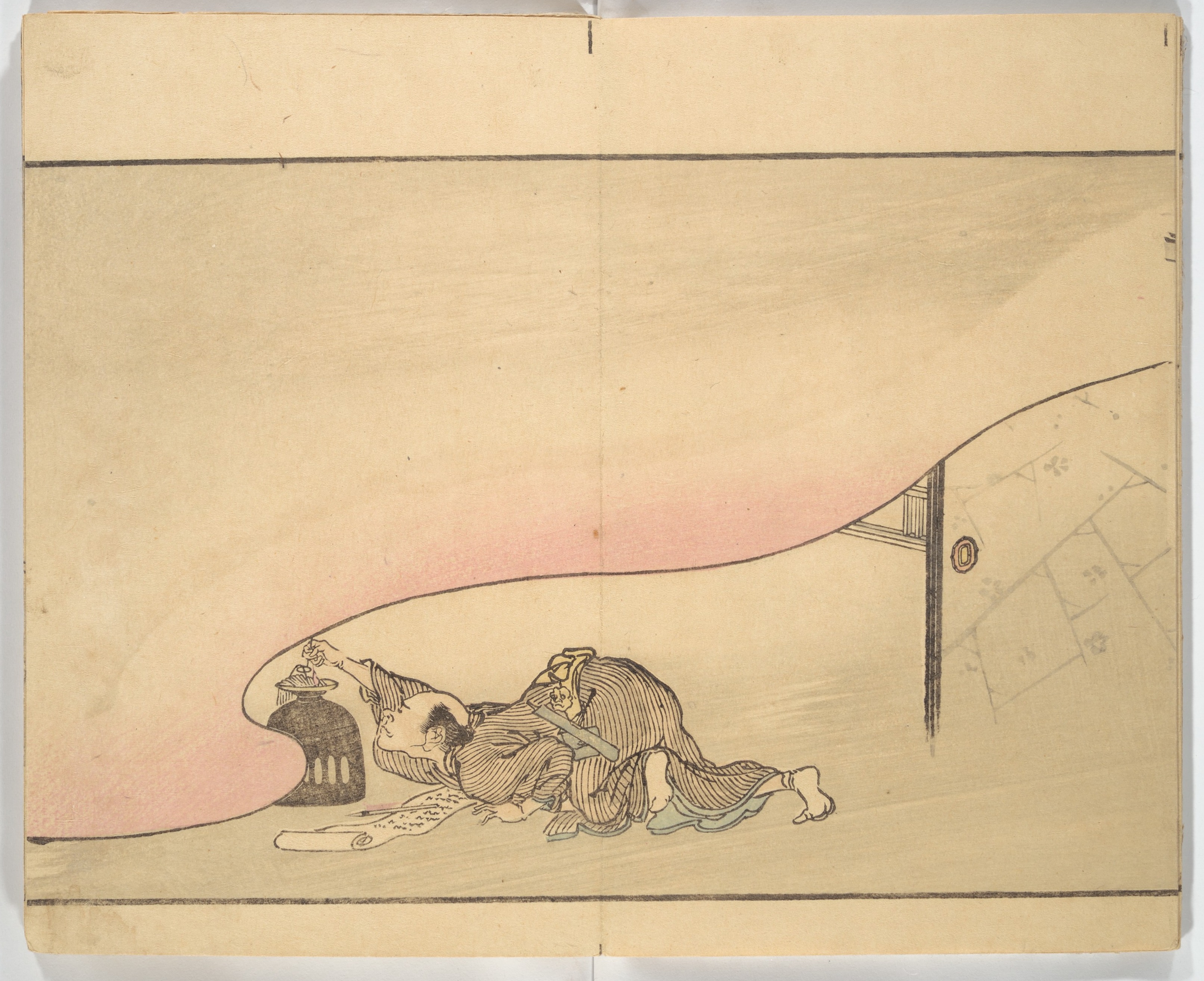

"A man, perhaps the artist himself, has set down his calligraphy brush and reaches to extinguish a lamp. Once darkness falls, the demons will appear."

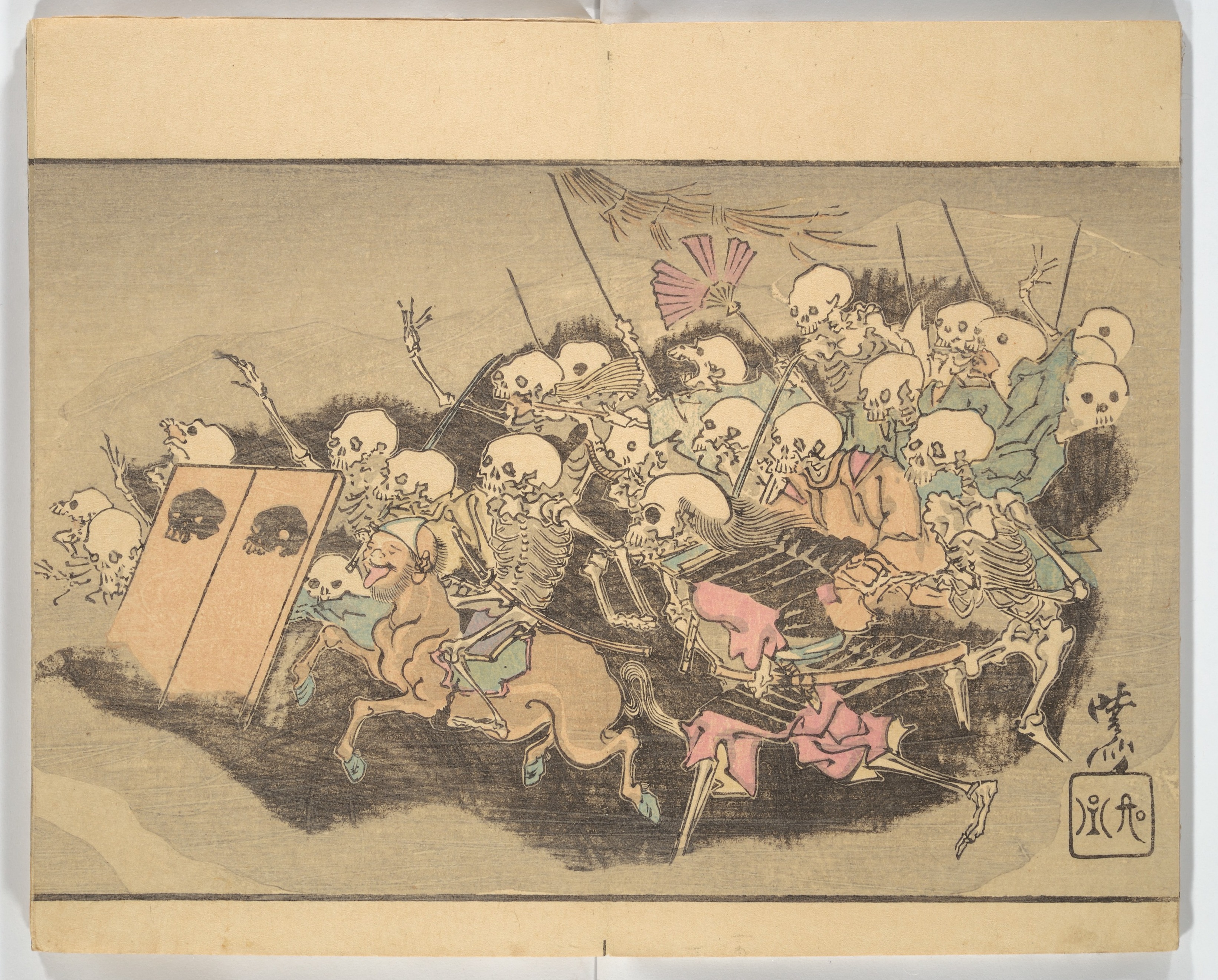

"A man, perhaps the artist himself, has set down his calligraphy brush and reaches to extinguish a lamp. Once darkness falls, the demons will appear."Kyōsai's demons are, without doubt, terrifying, often surreal in their appearance, weaponry, and movement. Many gallop off the paper into nightmares.

"Skeleton soldiers, a horse with the head of a man, and other monsters advance in the growing darkness."

"Skeleton soldiers, a horse with the head of a man, and other monsters advance in the growing darkness." "A one-eyed, malformed goddess, Benzaiten, is accompanied by an elephant, reptilian monsters, and, at left, the fierce Buddhist guardian Fudō Myōō holding a sword."

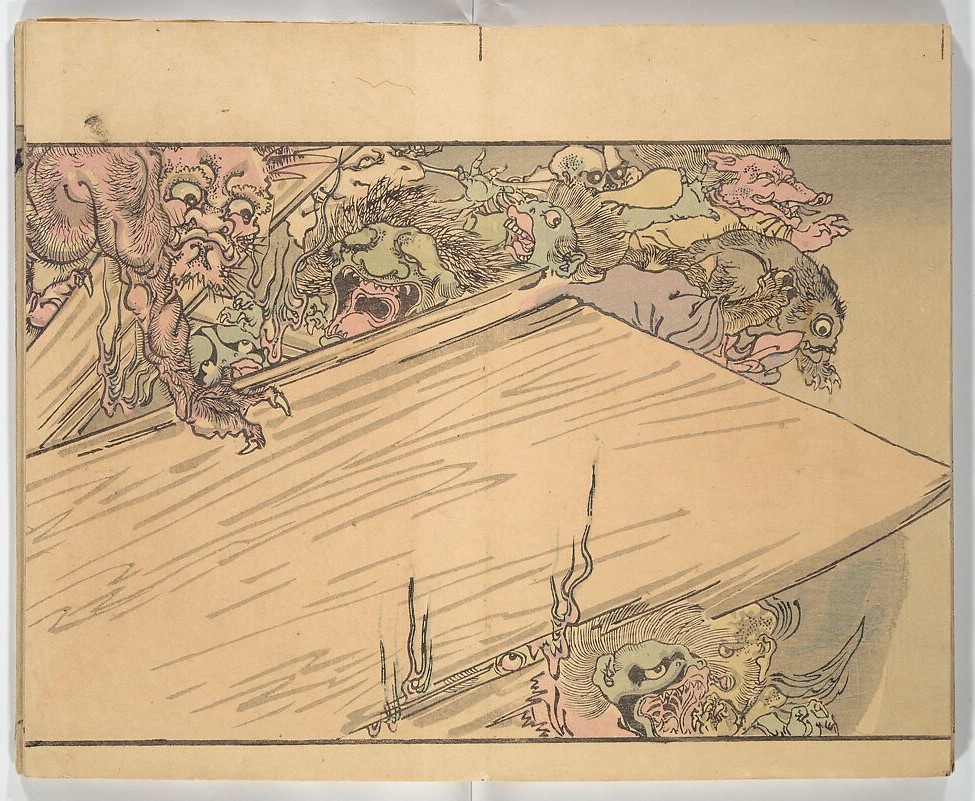

"A one-eyed, malformed goddess, Benzaiten, is accompanied by an elephant, reptilian monsters, and, at left, the fierce Buddhist guardian Fudō Myōō holding a sword."Equally, Kyōsai interweaves the illustrations with scenes of domesticity and ritual. Objects like instruments or cooking utensils turn into demons when the lights are out. This, as well as the exaggerated features and bright colors, renders the demons a tad comic. Are they terrifying or humorous? Such complexity is the nature of the then-developing comic and caricature genre and the prolific genius of Kyōsai.

"Ritual implements such as a monk’s fly whisk, boots, and a Buddhist gong become monsters."

"Ritual implements such as a monk’s fly whisk, boots, and a Buddhist gong become monsters." "Musical instruments, a lute (biwa) and zither (koto) appear as monsters."

"Musical instruments, a lute (biwa) and zither (koto) appear as monsters." "At right, a demon with a large nose and wings (tengū) carries panpipes (shō) and a pilgrim’s staff. His servant follows in wooden clogs (geta), with a wolf-like head and gaping mouth."

"At right, a demon with a large nose and wings (tengū) carries panpipes (shō) and a pilgrim’s staff. His servant follows in wooden clogs (geta), with a wolf-like head and gaping mouth." "A helmet for a court dance (bugaku), a chime (kei), ritual scepter (nyoi), and a folding fan turn into flying and running demons."

"A helmet for a court dance (bugaku), a chime (kei), ritual scepter (nyoi), and a folding fan turn into flying and running demons." "At right, a monster grips a feathered spear. An ogre follows, wearing a nobleman’s cap (eboshi) and carrying a similar spear."

"At right, a monster grips a feathered spear. An ogre follows, wearing a nobleman’s cap (eboshi) and carrying a similar spear." "At left, a small demon riding a badger with a stirrup on its head follows a hairy headed demon, and at far right, a shrouded, furry animal."

"At left, a small demon riding a badger with a stirrup on its head follows a hairy headed demon, and at far right, a shrouded, furry animal." "At right, a horned demon bears a spiked spear. At left, a beaked demon wields a wooden mallet over a one-eyed red demon’s head."

"At right, a horned demon bears a spiked spear. At left, a beaked demon wields a wooden mallet over a one-eyed red demon’s head." "At left, a monster holds up a mirror for an Otafuku-esque ghoul to apply black dye to her teeth. At right, a chubby faced figure carries a bag beside a three-eyed ghoul."

"At left, a monster holds up a mirror for an Otafuku-esque ghoul to apply black dye to her teeth. At right, a chubby faced figure carries a bag beside a three-eyed ghoul." "Animal demons, including one resembling a mad Shinto priest, carouse on an enormous bolt of cloth. A clawed monster hides underneath."

"Animal demons, including one resembling a mad Shinto priest, carouse on an enormous bolt of cloth. A clawed monster hides underneath." "At left, a beaked demon holds an umbrella monster, followed by a rope monster riding a hobbyhorse, and a hairy monster with a long, horned snout (kirin)."

"At left, a beaked demon holds an umbrella monster, followed by a rope monster riding a hobbyhorse, and a hairy monster with a long, horned snout (kirin)." "Everyday kitchen utensils such as lids, pots, and trivets have turned into monsters."

"Everyday kitchen utensils such as lids, pots, and trivets have turned into monsters." "Demons emerge from a large, wooden chest."

"Demons emerge from a large, wooden chest." "Monsters, including a badger wearing a courtier’s cap, carry Buddhist ritual implements, such as a magical scroll inscribed in Sanskrit, at far right."

"Monsters, including a badger wearing a courtier’s cap, carry Buddhist ritual implements, such as a magical scroll inscribed in Sanskrit, at far right." "Several monsters continue the procession, including one with a Buddhist monk’s alms bowl on its head."

"Several monsters continue the procession, including one with a Buddhist monk’s alms bowl on its head." "A row of demons, some with banners, another with a gourd-like head, march forward."

"A row of demons, some with banners, another with a gourd-like head, march forward." "A group of rowdy ghouls appears, including, at far right, a demon in a red robe with a hand scroll."

"A group of rowdy ghouls appears, including, at far right, a demon in a red robe with a hand scroll."Kyōsai's Pictures of One Hundred Demons (enjoy the full treasure here) is pure delight, with exquisite drawings and constant evidence of the unbridled mind that brought them into being.

From many accounts, Kawanabe Kyōsai was a character himself (he has a Mercurial crater [is that the adjective form of Mercury?] named after him.) My favorite tale is one super-human feat of production in 1880 in which Kyōsai while sobering up from a few bottles of rice wine, produced the provocative and highly original paper theatre curtain for a Kabuki show to open that night. The curtain was seventeen meters long and reimagined the main actors as monsters.

Kawanabe Kyōsai's stage curtain for the Shintomi Theatre. © The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum, Waseda University.

Kawanabe Kyōsai's stage curtain for the Shintomi Theatre. © The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum, Waseda University.Although the Meiji Era officially ended in 1912 with the death of the Emperor, feelings of change and division were far from soothed. In 1906 critic and scholar Okakura Kakuzō wrote his monograph on Teasim in English to acquaint the curious West with the harmony and purity of this century-honored ritual (and decry what he saw as often barbaric attitudes of the West towards Japan). Okakura wrote:

The long isolation of Japan from the rest of the world, so conducive to introspection, has been highly favorable to the development of Teaism. Our home and habits, costume and cuisine, porcelain, lacquer, painting—our very literature—all have been subject to its influence.

As late as 1934, novelist Jun'ichiro Tanizaki revisited Japanese aesthetics in his much-adored essays on beauty, purpose, and the patina of material. Their work was more than nostalgia; it was the re-positioning of Japanese culture that had ceased to find footing in the quick and vast influx of Western values and tastes.

Kakuzō's painted book was made available to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, aided by the Mary and James G. Wallach Foundation in 2013. The text in its entirety can be found here.