"Nothing to be afraid of - we'll get through this, all of us, together."

In 2010, Rebecca Solnit, a rough guide to unknown internal vagaries, made a close historical study of human actions in times of disaster and found numerous cases where people, their lives in upheaval, were able to support one another on a deeper, human level. With resources and systems momentarily destroyed, a raw human vulnerability was exposed. Asking for and providing help became a means of connecting and surviving. In a crisis, we are leveled to the same helplessness. Watching the systems and structures we take for granted disappear, we form new ones.

"There will be many books written about the year 2020," begins Zadie Smith (Born on October 25, 1975) in Intimations: "Historical, analytical, political as well as comprehensive accounts. This is not any of those."

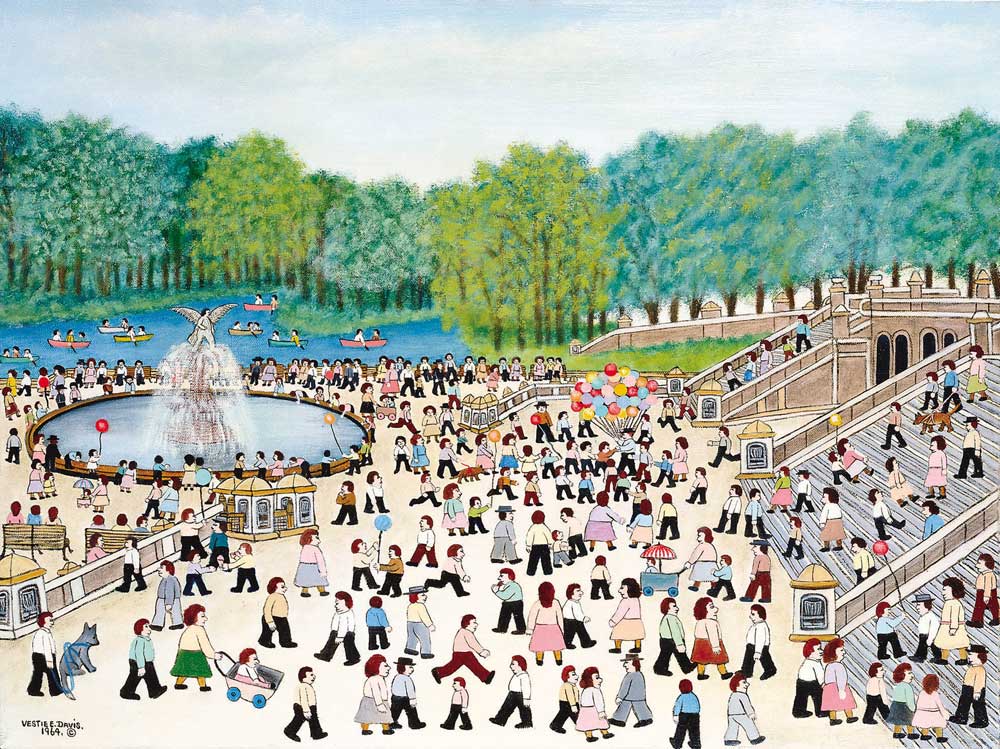

"Bethesda Fountain" by Vestie Davis (1964) courtesy of The American Folk Art Museum. Davis was an untrained artist whose New York people-populated venues were wildly popular in the 1950s and 70s.

"Bethesda Fountain" by Vestie Davis (1964) courtesy of The American Folk Art Museum. Davis was an untrained artist whose New York people-populated venues were wildly popular in the 1950s and 70s.Smith's essays, Intimations, intuit the original purpose of the essay, l'essais meaning to try in French. The literary form was named and popularized in the 1580s by Michel de Montaigne. Separate from the diary, or letters, the essay combined intellectual reasoning with anecdotal observations and strived toward a conclusion, usually self-revelation.

Smith's essay-formed process, written in the early days of the Covid-19 crisis in New York City, was to make emotional, practical, and even spiritual sense of the still-growing catastrophe. But are snap-shots of humans being human in the time of COVID-19 self-revelatory?

The funny thing about Barbara is she has a little dog whom she insists is a well-behaved dog but who, in reality, either barks or tries to bite pretty much everyone who comes near - except Barbara. New residents-grad students, and adjuncts - sometimes believe Barbara and bend down to pet him, but we got with the programme long ago and speak to Barbara only, giving Beck a wide berth. Barbara lives alone, she's coming up on seventy, surely, and she smokes the way I used to: with great relish and evident satisfaction. Perhaps because of all the cigarettes, she is slender and often seems somewhat frail. In the past ten years her tall, elegant body has become a little more hunched over and sometimes she uses a walker, but not always.

Like all good fiction writers Smith not only explains the idiosyncrasies of Barbara (who is real), but she also gives Barbara a past and suggestive - not all rosy - future. In her study of human actions during disasters, Solnit found informal civic connections formed at an immediate level, hand-to-hand helping. From that, we see another person so clearly, that we forget about ourselves.

Barbara's story continues:

There is an ideal, rent-controlled city dweller who appears to experience no self-pity, who knows exactly how long to talk to someone in the street, who creates community without overly sentimentalizing the concept - or ever saying aloud the word 'community' - and who always picks up after their dog, even if it's physically painful to do so. Whose daily breakfast is a cigarette and a croissant from the French place on the corner, although to accommodate her new walker Barbara now eats and smokes on the bench outside the hairdresser, properly intended for clients of the salon. But no one minds because this is Barbara and Beck we're talking about, regular in their habits and known to all. There she sat on that last day - I was passing with my little dog; a final chance for Maud to pee before we put her in the rental car - and I could see Barbara was preparing to bark one of her ambivalent declamations at me, about the weather or a piece of prose, or some new outrage committed by the leader of a country which, in Barbara's mind, only theoretically includes her own city.

Instead, she sucked hard on her cigarette and said, in a voice far quieter than I'd ever heard her use: "Thing is, we're a community, and we got each other's back. You'll be there for me, and I'll be there for you, and we'll all be there for each other, the whole building. Nothing to be afraid of - we'll get through this, all of us, together.

"Nothing to be afraid of - we'll get through this, all of us, together," of the thousands of phrases from Barbara, Smith shared this. Why? For the uncertainty of the statement. During COVID-19, unlike almost every other disaster since the postbellum Spanish Influenza in the 1900s and the black plague in the 1600s (Daniel Defoe's journalistic account of the plague feels hauntingly like Covid), people were thrust apart.

What I read from Smith's close observation is this: what did isolation mean for the Barbaras, those who lived alone, aged alone, and hung their day on taking the dog out of the apartment? What would happen to the Becks, dogs who bite everyone but their owner?

This invisible isolation draws me to Jan Enkelmann's Pause, a photographic capture of London in lockdown. It is easy to be capsized by beauty amidst the wreckage, the architecture, and the light, but we should also remember what is not there; the grim sadness of people apart.

Leicester Square during London's lockdown, photograph by Jan Enkelmann.

Leicester Square during London's lockdown, photograph by Jan Enkelmann. In the book, Enkelmann notes:

"I locked my bike to railings on Charing Cross Road and walked across Leicester Square, where the huge LED screens of the big cinemas were either turned off or displaying messages asking people to stay at home. I feared I might be stopped by police at any moment and questioned as to what I was up to. I was reluctant to get my camera out. But there was no one about. The only people I encountered were a few food delivery drivers on their bikes and scooters, and the homeless. I spoke with a shivering couple in Piccadilly Circus. They were actively hoping to be picked up by the police as they had nowhere to go and begging had become pointless.

In her essay-ic amble, Smith eventually returns to her mission of self-revelation and, in a very fluid and undiscussed way, wonders if Barbara is correct. Would we all be ok? Are we really all in this together?

Smith continues:

I turn the corner onto Broadway and find it empty - which is news, at this point, as I couldn't see it from our perch on the eleventh floor. The bank is dark beyond the vestibule, with only ATMs open for business. But it is loud in here because one of my characters is here, Myron, from a story called 'Words and Music'. I haven't seen him since long before I wrote that story and I'm very glad to see he is alive and in such a good voice, as it is fair to assume that a man in his position - homeless, legless - faces an existential battle most days. I don't greet Myron, because he is on the phone, because the time of fictional playfulness seems over, and because his name is not really Myron. Nor, as far as I know, was he ever a particular fan of disco - a trait I took the liberty of bestowing upon him. I have no idea what music he likes. Although I do remember, when it was my turn to push him down Broadway one time, he heard me singing some Stevie under my breath and joined in.

Zadie Smith, 2014.

Zadie Smith, 2014.I've written quite a bit on The Examined Life about brotherly love and brotherhood, exploring our demonstrated need to form an identifying social group and whether we have an innate desire to give the last of our food to another. I've also explored solitude, loneliness, and isolation - three things that, while not mutually exclusive, are notably different. Each is textured by our relationship with ourselves and one another.

COVID-19 and specifically the lockdowns threw all of us into something that felt exhaustively new, unchartered. A space of loneliness, fear, longing, and physicality unknown by our instinctual beings. This hitherto unexperienced form of vulnerability is palpable in Smith's words, especially in this beautiful passage.

“Is that Sadie? You don't remember me, do you? I'm – 's mum. I don't think she was in your year, as it goes... Know your mum, tho'! Knew you when you were a baby. I saw your mum in the high street not long ago, looking well. She didn't say you was back. Yeah, we're doing all right. Still Stonebridge, still in the Ends..." I had just got off a bus and was heading home, but when someone calls me by my name, by my real name, I listen very closely. I attend to the speaker as an auntie and an elder. And here was an obvious Auntie: mighty-bosomed in a V-neck T-shirt she had deliberately taken a pair of scissors to (in order to drastically deepen the décolletage) and wearing a pair of dark indigo jeans, studded with diamanté, skin-tight. 'Hugging every curve,' as they say. The whole back line of her body spoke of power and youth, although, by the local coordinates she was giving me - whose cousin knew which sibling's girlfriend at what time – I understood she must be an elder, even if she didn't remotely look like one. I took my backpack off and sat down on the paltry four inches of plastic that long ago replaced the sturdy bus-stop benches of my childhood. I got ready to receive whatever was coming. It was a bounty: You know where I'm headed? Doctor's. You know why? It's this bloody menopause. I sympathized, but as it turned out, I had completely the wrong end of the stick: Nah, I'm going in there to DEMAND he brings it on! I'm fifty-eight! What am I still doing with periods?”

The familiarity of this encounter, the absolute, almost - absurd mundanity about it. I exhaled a breath I didn't know I was holding. It is funny. 'Maybe things will be ok after all?' I imagine Smith thinking as she wrote.

During Covid - 19, I remember pretty clearly an elderly neighbor who went on at me about an unclipped jasmine vine that had hurdled the fence and shaded his otherwise ebullient rose patch. I smiled at the nonsense and then clipped the jasmine because it was not about the jasmine or the roses. It was about being sick of Covid and wanting to return to normalcy where unbloomed prize roses were a huge neighborly issue.

St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York City. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York City. Photograph by Ellen Vrana.Intimations, Smith's lovely project of essays that also gave us thoughts on the role of an artist in society, was a compilation of ideas inspired, Smith tells us, by the need to "be overheard."

Early on in the crisis, I picked up Marcus Aurelius and, for the first time in my life read his Meditations not as an academic exercise, nor in pursuit of pleasure, but with the same attitude I bring to the instructions for a flat-pack table - I was in need of practical assistance. (That the assistance Aurelius offers is for the spirit makes it no less practical in my view.)... I came out with two invaluable intimations. Talking to yourself can be useful. And writing means being overheard.

I've said it elsewhere and repeat it here: Meditations are exceptional. Its author, a Roman emperor, and Stoic, did not know genealogy, the universe, the earth's limits, or any atomic concepts and yet ventured a sublime conclusion about our oneness that holds today: "We are born for cooperation."

All of Smith's royalties from Intimations sales benefitted The Equal Justice Initiative and Covid-Relief for NYC, which are the kind of organizations you want to strengthen in exponential proportionality to people's needs. To cross that which divides us, to be seen and overheard, to have someone - even a peevish dog - witness our lives as we droop and slope toward the earth is all any of us want. This need was heightened in the echoing Covid lockdowns, social distancing, and general fear of an unknown. In seeking to be overheard herself, Smith also gave that gift to others.