"No matter how daring or cautious you may choose to be, in the course of your life, you are bound to come into direct physical contact with what's known as Evil. The surest defense is extreme individualism, originality of thinking."

In the spring of 1984 - a year haunted by George Orwell's pseudo-fictional warning of totalitarianism - Nobel laureate, Russian refugee, and poet Joseph Brodsky (May 24, 1940 - January 28, 1996) gave a commencement speech to the graduating class of Williams College on the palpable presence of evil.

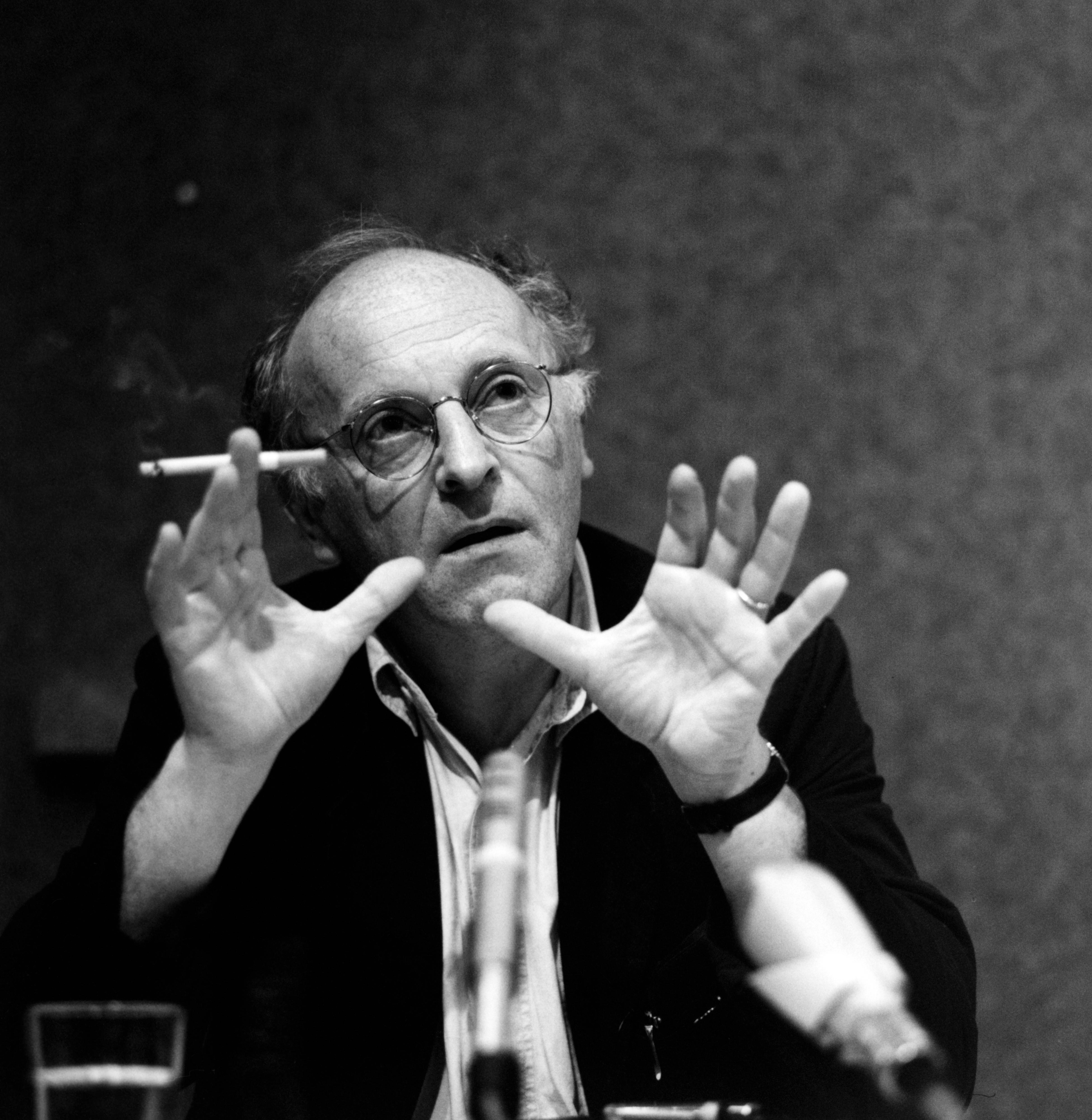

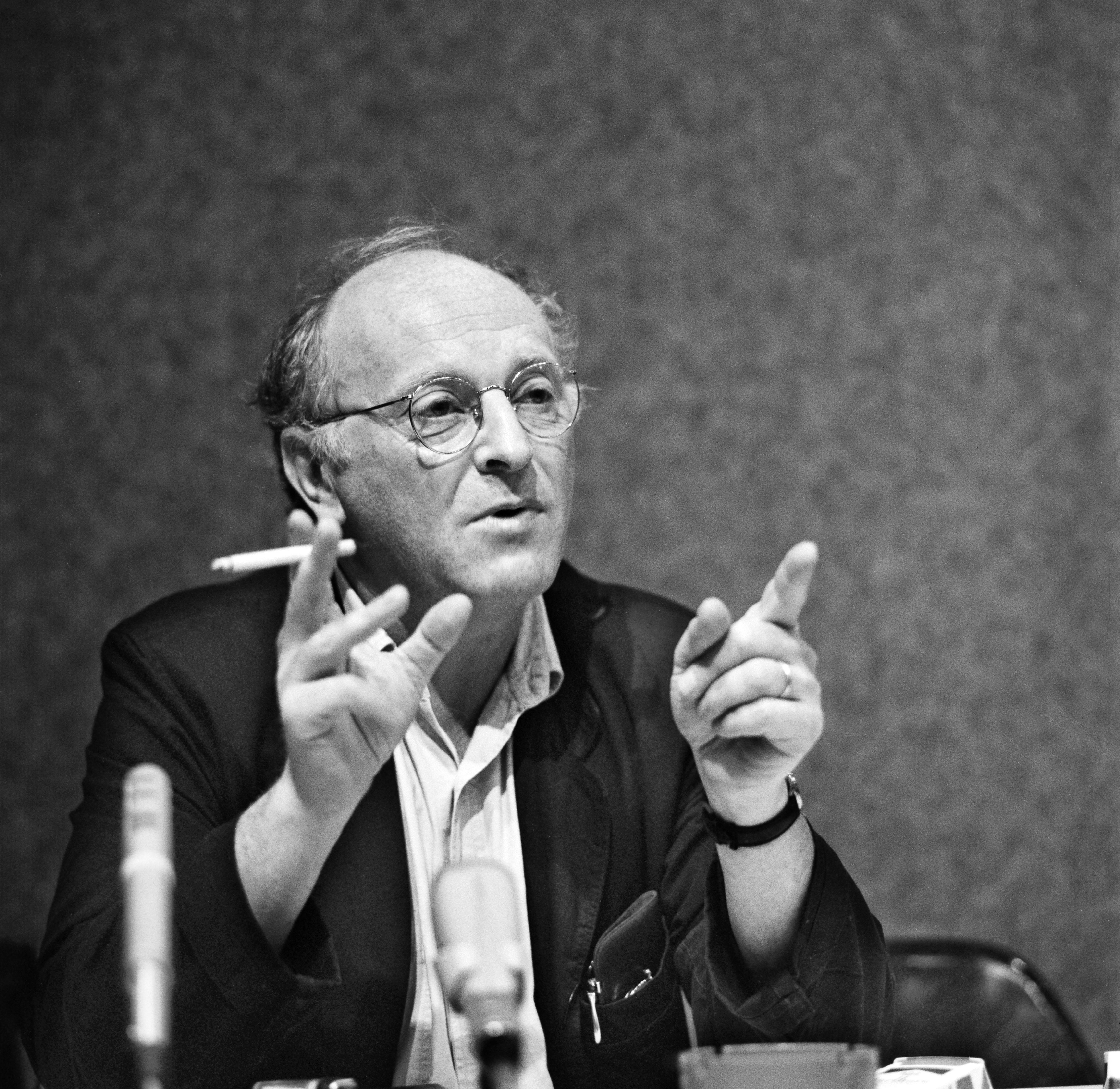

Joseph Brodsky in 1992.

Joseph Brodsky in 1992.Brodsky's message, published in Less Than One: Selected Essays, is not to look without but to look within. There is a double-handedness in being human: we can be multitudes at once, even good and evil. Our own capacity for evil is real and comes from fear, pain, and unrealized intolerance. If we fail to see these things within ourselves, we will miss - and thus accept - them in others.

Buddhist teacher Pema Chödrön, although drawing from a different theological background than Brodsky, drew a similar lesson of human failing: "When the rivers and air are polluted, when families and nations are at war, when homeless wanderers fill the highways, these are traditional signs of a dark age. Another is that people become poisoned by self-doubt and become cowards."

What darkness awaits on the other side? Photograph by Ellen Vrana.

What darkness awaits on the other side? Photograph by Ellen Vrana.Brodsky tells us: "No matter how daring or cautious you may choose to be, in the course of your life, you are bound to come into direct physical contact with what's known as Evil." He warns of not just a feeling of evil but its physical reality.

I mean here not a property of the gothic novel but, to say the least, a palpable social reality that you in no way can control. No amount of good nature or cunning calculations will prevent this encounter. In fact, the more calculating, the more cautious you are, the greater is the likelihood of this rendezvous, the harder its impact. Such is the structure of life that what we regard as Evil is capable of a fairly ubiquitous presence if only because it tends to appear in the guise of good. You never see it crossing your threshold announcing itself: "Hi, I'm Evil!" That, of course, indicates its secondary nature, but the comfort one may derive from this observation gets dulled by its frequency.

Evil might exist outside humanity, on the opposite side of a boundary of goodness against which we push and occasionally fortify, but it does not exist outside the body. It can be activated so secretly, so imperceptibly, we barely notice. It grows through an aperture of cowardice or fear and feels, in a way, familiar, even comforting. In words that ring as true today as they did in 1984, Brodsky reminds us the more shallow our convictions, the less tested they are, the more invisible their flaws and faults will be.

To base ethics on a faultily quoted verse is to invite doom or else to end up becoming a mental bourgeois enjoying the ultimate comfort: that of his convictions. In either case (of which the latter with its membership in well-intentioned movements and nonprofit organizations is the least palatable), it results in yielding ground to Evil, in delaying the comprehension of its weaknesses. For Evil, may I remind you, is only human.

Evil is real. What does that mean in a world that is virtual? Where relationships and art are expedited and exploited by computer programming language and machine learning? Where is our modern Orwell to guide us into what the future might become? As the center falls apart, wisdom that originated with W. B. Yeats a century ago and has been revisited since by Joan Didion, who rights our alignment?

We normalize the absurdity faster than we can register its demanding conformity. Remember when Covid was vastly unknown and terrifying? What is it to us now? What does our desensitization mean? How do we mobilize our senses to "see" evil when they are so easily dulled? How do we look in the mirror and see what is there when there are no mirrors in this world except those brandishing filters?

Begin, Brodsky advises, by zooming in on the convictions, we take for granted:

"A prudent thing to do, therefore, would be to subject your notions of good to the closest possible scrutiny, to go, so to speak, through your entire wardrobe checking which of your clothes may fit a stranger. That, of course, may turn into a full-time occupation, and well it should. You'll be surprised how many things you considered your own and good can easily fit, without much adjustment, your enemy. You may even start to wonder whether he is not your mirror image, for the most interesting thing about Evil is that it is wholly human. To put it mildly, nothing can be turned and worn inside out with greater ease than one's notion of social justice, civic conscience, a better future, etc. One of the surest signs of danger here is the number of those who share your views, not so much because unanimity has the knack of degenerating into uniformity as because of the probability-implicit in great numbers-that noble sentiment is being faked.

Is it possible to have both tenderness and critical self-reflection? Possible, imperative, and also at the root of everything that matters. It is a careful blend of self-awareness and self-hardening that allows us to recognize and slay Evil. The self-love that leads to self-acceptance, and individualism.

Brodsky continues:

"The surest defense against Evil is extreme individualism, originality of thinking, whimsicality, even if you will eccentricity, that is, something that can't be feigned, faked, imitated; something even a seasoned impostor couldn't be happy with. Something, in other words, that can't be shared, like your own skin: not even by a minority. Evil is a sucker for solidity. It always goes for big numbers, for confident granite, for ideological purity, for drilled armies and balanced sheets. Its proclivity for such things has to do presumably with its innate insecurity, but this realization, again, is of small comfort when Evil triumphs."

Totalitarianism is a system that exists to annihilate everything it is not. It does not rise in those who disagree but in those who fail to listen. Within us is the capacity for Evil, to turn our fear into hate, a process Toni Morrison called "othering." Brodsky's mission for the graduating class of 1984 (a class that included a beloved family member of mine) is that we must be more inventive. Stronger. More robust in examining ourselves and others.

What perhaps relieves one from a charge of treason or, worse still, of projecting the tactical status quo into the future, is the hope that the victim will always be more inventive, more original in his thinking, more enterprising than the villain. Hence the chance that the victim may triumph.

Despite its fruitful skirmishes and often-moving frontline, I think Evil has yet to triumph. At the very least, as I write this post and you see it and believe there is a well-intentioned human behind it, and a well-meaning person receives it, we commune. Is that a form of goodness?

Evil always lurks; it never dies. If we fail to remember that, ours will be a failure of imagination, not will—a failure of empathy, not technology.

I shall define neither evil nor good; both should enjoy perpetual existence in question, not answer. Instead, let's focus on creative invention, divisive art, and resplendent individuality: like poet Ocean Vuong's harsh yet loving self-examination, Mark Hearld's riotous creation, and my collection of those who rebel with joy. As you examine the strength and base of the goodness that holds you up, take comfort in the brightness of the human spirit in times of disaster, Maya Angelou's poetic love summoned from pain, and Charlie Mackesy's rarefied kindness.