“Our modern need to dull the sawtooth edges of many afflictions has banished the harsh old-fashioned words: madhouse, asylum, insanity, melancholia, lunatic, madness. But never let it be doubted that depression, in its extreme form, is madness."

In 1956, American novelist and civil rights activist James Baldwin wrote the following note to his childhood friend and editor, Sol Stein: "I thought I was sick, and indeed I was, but it turned out to be only a breakdown. About breakdowns, baby, there is nothing to say, nothing one can say while it's happening...." Baldwin excuses his behavior, reckons the experience was valuable, and then promises a "real letter" to come. In Stein's memoir of their decades-long friendship, he wrote this was the only time Baldwin spoke of the breakdown.

Typically, mental health issues - acute or chronic - happen outside the pages of an artist's work, on the margin of a margin of a life. Something that has happened or is happening over there. I have had Bipolar II my entire adult life, and I always leave it at home. I don't bring it to The Examined Life, school drop-offs, or family reunions. I sideline it to live an everyday life and protect others. Until I cannot, and then I withdraw to tend it. Those with mental illness constantly imply: "Yes, I have it. But it is not with me now; do not fear."

Did we agree to this? Do those of you without mental illness know what it looks like? Do you want to? The reality of mental illness is terrifying, messy, angry, immovable, and inscrutable. It might seep into poetry or art, but honestly, it is best left in the privacy of home.

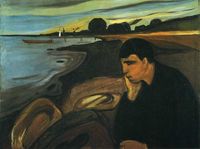

"Melancholy" by Edvard Munch, 1894

"Melancholy" by Edvard Munch, 1894And then we have William Styron (June 11, 1925 – November 1, 2006), American author of Sophie's Choice and The Confessions of Nat Turner and Baldwin's colleague (they were part of a group that founded the literary journal Paris Review). Styron's Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness is a stunning piece of confession literature about his 1985 depressive episode.

It was not really alarming at first, since the change was subtle, but I did notice that my surroundings took on a different tone at certain times: the shadows of nightfall seemed more somber, my mornings were less buoyant, walks in the woods became less zestful, and there was a moment during my working hours in the late afternoon when a kind of panic and anxiety overtook me, just for a few minutes, accompanied by a visceral queasiness - such a seizure was at least slightly alarming, after all. As I set down these recollections, I realize that it should have been plain to me that I was already in the grip of the beginning of a mood disorder, but I was ignorant of such a condition at that time.

Time is immeasurable in depression; it keeps a cadence of light, energy, hope, and despair. The hours of the clock rarely register. And yet, there is a progression from mental clarity to a tortured obfuscation. Styron details this change beautifully and tragically.

I had now reached that phase of the disorder where all sense of hope had vanished, along with the idea of futurity; my brain, in thrall to its outlaw hormones, had become less an organ of thought than an instrument registering, minute by minute, varying degrees of its own suffering. The mornings themselves were becoming bad now as I wandered about lethargic, following my synthetic sleep, but afternoons were still the worst, beginning at about three o'clock, when I'd feel the horror, like some poisonous fogbank, roll in upon my mind, forcing me into bed. There I would lie for as long as six hours, stuporous and virtually paralyzed, gazing at the ceiling and waiting for that moment of evening when, mysteriously, the crucifixion would ease up just enough to allow me to force down some food and then, like an automaton, seek an hour or two of sleep again. Why wasn't I in a hospital?

Styron's words poignantly parallel those of Emma Mitchell, a British artist and nature writer whose journal of depression (and the mending power of nature) escorts us through depression's descents. Ultimately, untreated, depression ends in the same locale: measuring pain against oblivion. A valuation made, remember, by a mind unaware and out of control.

The manuscript of Darkness Visible begins, "Early in the spring of 1986, I began to slowly recover from a malevolent mental illness." Learn more.

The manuscript of Darkness Visible begins, "Early in the spring of 1986, I began to slowly recover from a malevolent mental illness." Learn more.Styron continues:

Death, as I have said, was now a daily presence, blowing over me in cold gusts. I had not conceived precisely how my end would come. In short, I was still keeping the idea of suicide at bay. But plainly the possibility was around the corner, and I would soon meet it face to face.

[...]

Our perhaps understandable modern need to dull the sawtooth edges of so many of the afflictions we are heir to has led us to banish the harsh old-fashioned words: madhouse, asylum, insanity, melancholia, lunatic, madness. But never let it be doubted that depression, in its extreme form, is madness. The madness results from an aberrant biochemical process.

Baldwin wrote to Stein, "It seems I want to live." The language is casual, but for Stein's benefit, not because Baldwin took that decision casually - or that he even made a decision in the first place. Styron, too, "seemed to want to live." And he did until his natural death in 2006. He is honest that no one thing onsets depression, and even more importantly, no one thing abates it (or causes individuals to take their own lives).

I was sixty when the illness struck for the first time, in the "unipolar" form, which leads straight down. I shall never learn what "caused" my depression, as no one will ever learn about their own. To be able to do so will likely forever prove to be an impossibility, so complex are the intermingled factors of abnormal chemistry, behavior and genetics. Plainly, multiple components involved - perhaps three or four, most probably more, in fathomless permutations.

At the end of 1985, Styron was hospitalized, and in 1986, he emerged functional enough to write up his fractured notes into what would become Darkness Visible.

William Styron in 1952.

William Styron in 1952.Depression is a spinning gyre of madness and gravity that pulls the sufferer to the center. At the center are psychosis and death. Styron's account has transparency and vulnerability but equally a great deal of intellectual distance. It is a mind undergoing depression, but it is also a lucid, non-depressive mind trying to make sense of that depression. John Keats's poetic rumination on melancholy and Vincent van Gogh's self-confessions with his brother are equally perceptive and painful.

But an account even closer to the gyre's center is the diaries of Russian ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky. During a prolonged breakdown that ended in a fifty-year hospitalization, the world’s most famous dancer writes and draws one of the best records of an artist in psychosis. Depression should be dark, not inscrutable.