"Mirrors show everything but themselves." Where do we look to see ourselves fully?

As we fling ourselves headfirst into the universe, asking unspoken questions like “Do I exist?” “What am I?” “Who am I?” very few things respond as fast and accurately as a mirror. Sight is our primary sense to register information, and in the mirror, we see ourselves. There we are, that we are.

We see ourselves in mirrors, but what do we know of ourselves?

My daughter flirted with the threshold of self-awareness around six months ago when she first saw herself in the mirror. She went nuts. She flapped like a flamingo. She then saw herself flapping like a flamingo and began barking and flapping like a puppy-flamingo hybrid.

Did my daughter see herself in the mirror? Did she think, “I am here”? Or did she merely see something entertaining and react? (It was thoroughly entertaining.)

Besides humans (older than six months, we assume), there is a list of animals that can recognize themselves in mirrors. This list is expanding so rapidly that scientists are now wondering if the test they use—a dot on the face that animals try to remove—is inept. A fish passed it recently. The dolphins migrated in protest.

It’s complicated.

Intelligence isn’t a binary concept, however; it’s a continuum. Bird intelligence involves complex social structures, food caching and retrieval, usage of tools, subtextual communication, and, for our magpie, self-recognition.

In many cases, we assume we can map and understand animal intelligence, but what if we can’t? What if our knowledge of their intelligence is bounded by our own? Dutch primatologist, Frans de Waal, a man who has done much to place and link humans and apes on this intelligence continuum, explores this unexpected but vital question in Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are.

There is a spirit of something—existence between the body and the mind.

My daughter didn’t just flap. She flapped, saw herself flapping, and knew it was she who was flapping. That is incipient self-awareness. Pretty soon, like most humans, she’ll look to a mirror to deliver honest truths about her appearance, her self.

We learn to trust mirrors early on. Rely on them entirely.

Consider the Robert Lowell poem, “Waking in the Blue.” Lowell, leader of the confessional poets of the mid-20th century, struggled with manic depression his entire life and spent many interludes in psychiatric hospitals. In that space, specifically McLean Hospital outside Boston, he saw his physical self bent and twisted in the “metal shaving mirrors.”

The night attendant, a B.U. sophomore,

rouses from the mare’s-nest of his drowsy head

propped on The Meaning of Meaning.

He catwalks down our corridor.

Azure day

makes my agonized blue window bleaker.

Crows maunder on the petrified fairway.

Absence! My heart grows tense

as though a harpoon were sparring for the kill.

(This is the house for the ‘mentally ill.’) After a hearty New England breakfast,

I weigh two hundred pounds

this morning. Cock of the walk,

I strut in my turtle-necked French sailor’s jersey

before the metal shaving mirrors,

and see the shaky future grow familiar

in the pinched, indigenous faces

of these thoroughbred mental cases.

From Robert Lowell’s “Waking in the Blue”

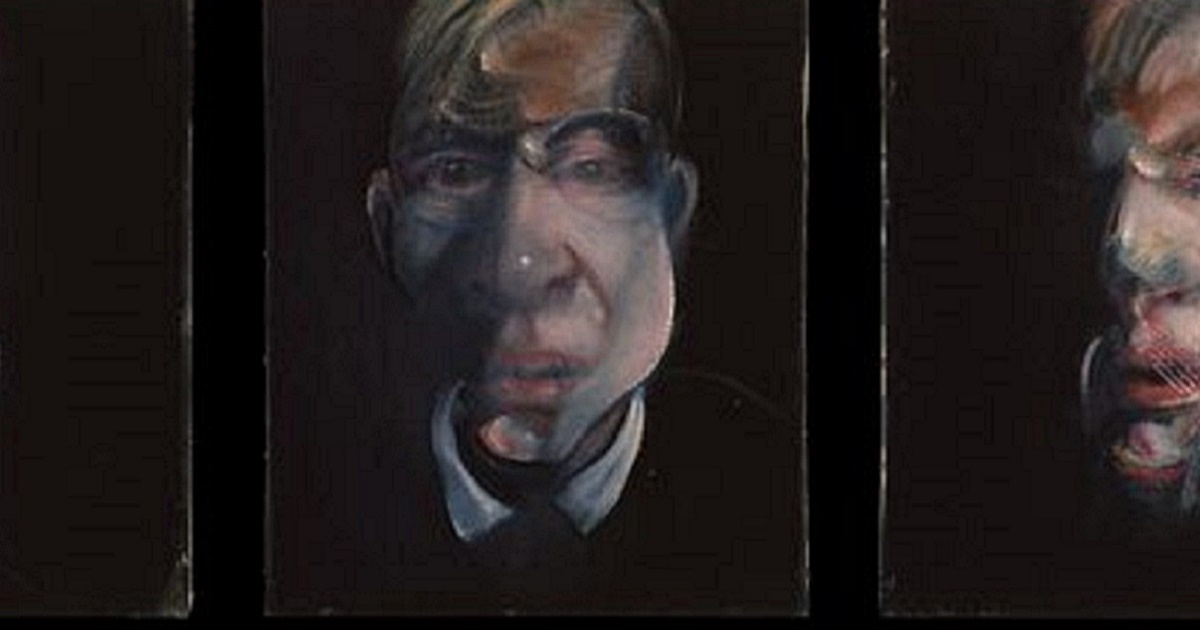

Mirrors of metal so they couldn’t become shards. Metal that returned “pinched” reflections and “shaky futures.” Twisted and blotched like a Francis Bacon portrait. Lowell saw his fractured self in the mirror. Is that who he was?

Francis Bacon’s “Three Studies for a Self-Portrait” 1979-80. Learn more.

Francis Bacon’s “Three Studies for a Self-Portrait” 1979-80. Learn more.Francis Bacon was a modern British artist whose work electrified its viewers, simultaneously delivering shock and feeling with features that looked human, mechanical, and dreamlike. Bacon acknowledged his art was self-representational:

Autobiographical? Well yes, inevitably, it’s about my life, at some level. It’s filled with my thoughts about things. And yet when I’m in the middle of it, I forget about everything, about myself and about friends and things that have happened. That might sound as if I’m talking about inspiration, but it’s not that. … I just get the bits of paint down and hope they suggest a way I can make something that looks as if it’s come directly off the nervous system.

From Michael Peppiatt’s Francis Bacon in Your Blood

In the mad dash to “get the bits of paint down,” Bacon created work that reflected sight but not visual. Something deeper, emotions drawn directly from his nervous system and passed intravenously (intranervously?) to our subcutaneous essence. In that way, Bacon was mirroring himself—and perhaps mirroring everyone. Is that a realistic portrayal of humanity?

If I could draw my emotions, soul, and psyche, it might look like a Bacon portrait. Mechanical, human, and dreamlike. Or at least a reflection in a metal shaving mirror.

But that’s not how I appear. What about appearance?

Terry Gross has interviewed thousands of people in her 40 years hosting NPR’s Fresh Air. Gross has said that the most common question from the audience was what she looked like. Why? Does what she looks like tell us more about her than what she says on the air and in interviews? Our appearance is a reflection without deeper consideration—a physical without a self.

This distinction is the crack through slips the concept of a double—this double, this us that appears precisely like us, which is not us.

Suggested or stimulated by reflections in mirrors and in water and by twins, the idea of the Double is common to many countries. It is likely that sentences such as A friend is another self by Pythagoras or the Platonic Know thyself were inspired by it. In Germany this Double is called a Doppelgänger, which means ‘double walker.’ In Scotland there is the fetch, which comes to fetch a man to bring him to his death; there is also the Scottish word wraith for an apparition thought to be seen by a person in his exact image just before death. To meet oneself is, therefore, ominous.

Has anyone written more about mirrors—their power and limitations—than Borges? This Argentine writer, poet, essayist, and man stepped back from life and marveled that we are alive. A man who must have seen himself from a distance, like a mirror would.

Except, Borges did not see himself in a mirror. Not only did he suffer from extreme shortsightedness—and, at the end of his life, blindness—he also had a lifelong dislike (he even uses the word “fear”) of mirrors and strictly avoided them. When asked about his usage of mirrors as an image, he answered:

Well, that also goes with the earliest fears and wonders of my childhood, being afraid of mirrors, being afraid of mahogany, being afraid of being repeated. […] The feeling came from my childhood.

The double is us, but it isn’t us. It is us without the self.

I am fascinated by the double, except, bizarrely, I imagine myself as the reflection, not the original. A Midwestern-bred need to please makes me “mirror” others rather than project myself.

American essayist Rebecca Solnit, a student of human boundaries and compassion, wrote she was made to feel she was the “mirror” of her mother. Solnit grieves for her lost self.

Who was I all those years before? I was not. Mirrors show everything but themselves. […] She thought of me as a mirror but didn’t like what she saw and blamed the mirror. When I was thirty, in one of the furious letters I sometimes composed and rarely sent, I wrote, “You want me to be some kind of a mirror that will reflect the self-image you want to see – perfect mother, totally loved, always right – but I am not a mirror, and the shortcomings you see are not my fault.

From Rebecca Solnit’s The Faraway Nearby

A mirror is where we meet and see our embodied self. A mirror tells us that we are. Frozen in time. Mirrors don’t capture the past or the future, but they do reflect the present. As long as we stay in the now, there will be no then. Do we ever feel more alive than in those moments when we’re confident we’re not dead?

As I dance around these issues, throw a few into the universe, gently strike the concept of a mirror, and wait for a chime, one sure thing—despite the intelligent attempts of the magpie—is that self-awareness, mirror or not, is wondrously unique to human beings.

A conduit to self-knowledge that is useful is E.F. Schumacher’s categorization of knowledge into four collectively exhaustive entities: 1) knowing about I feel, 2) knowing how you feel, 3) knowing how I look, and 4) knowing how you look.

In this hierarchy, a mirror will tell us maybe three and four. But hardly the first. Emotions are instinctively expressed on our face and movements but those are basic at best and hardly representative of a ‘being.’

Schumacher was a German economist who spent his life inserting human interests and psychology into material sciences. An exceptional thinker and writer.

Mirrors might tell us that we are, but as Borges knew well, they don’t tell us who we are. Only deep contemplation and examination of the miracle of life, our existence, and, ultimately, our nonexistence can do that.

Self-knowledge is beyond the mirror.