"In this short treatise I propose great things for inspection and contemplation by every explorer of Nature."

Galileo Galilei's (February 15, 1564 – January 8. 1642) Sidereus Nuncius (The Sidereal Messenger or The Starry Messenger) was a landmark publication in 1610 that changed humankind's understanding of the moon, stars, sun, universe, and, by extension, our position among them. In the book's inscription, Galileo directs the work to "explorers of Nature." Though the publication was intended for the de Medici family and became their property, Sidereus Nuncius was also available to other Latin-educated scholars.

In this short treatise I propose great things for inspection and contemplation by every explorer of Nature. Great, I say, because of the excellence of the things themselves, because of their newness, unheard of through the ages, and also because of the instrument with the benefit of which they make themselves manifest to our sight. Certainly it is a great thing to add to the countless multitude of fixed stars visible hitherto by natural means and expose to our eyes innumerable others never seen before, which exceed tenfold the number of old and known ones.

Sidereus Nuncius also introduced the telescope as a legitimate means of technical observation. The unseen details of the sky were suddenly visible.

Facsimile of the telescope by Galileo with the main tube measuring 2 feet, 8 1/2 inches, and magnification of 21 times. Made by Cipriani and purchased from the Museo di Fisica e Storia Naturale, Florence, Italy, in 1923. Learn more.

Facsimile of the telescope by Galileo with the main tube measuring 2 feet, 8 1/2 inches, and magnification of 21 times. Made by Cipriani and purchased from the Museo di Fisica e Storia Naturale, Florence, Italy, in 1923. Learn more.Wrote Galileo of this remarkable device:

... A new contrivance of glasses [occhaile], drawn from the most recondite speculations of perspective, which renders the visible objects so close to the eye and represents them so distinctly that those that are distant, for example, 9 miles appear as they were only 1 mile distant.

Galileo's telescope, fashioned with specially cut lenses and advanced optics knowledge, allowed him to view the moons of Jupiter (previously considered stars) and the mountains and valleys of the earth's moon.

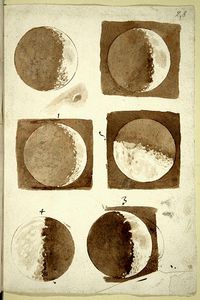

Galileo Galilei's Phases of the Moon shows earth-like topography demonstrating the imperfection of these heavenly bodies.

Galileo Galilei's Phases of the Moon shows earth-like topography demonstrating the imperfection of these heavenly bodies. When Galileo looked through his telescope in 1609, there were essentially two prevailing schools of thought about non-earth structures: The Ptolemaic system considered the earth the center of the universe and everything above part of the unchanging divine, and the Copernican model, conceived by the eponymous Polish mathematician a century before Galileo, considered both the sun and earth as fixed centers of the universe.

Both theories had weaknesses, and neither had been proven using strict observational measurement.

Galileo did not prove the Copernican system, but he introduced significant doubt in the logic of the geocentric theory. (His subsequent study of the phases of Venus—only observable with a telescope—proved the Ptolemaic system impossible.) He also disproved the Aristotelian logic that bodies in the heavens were unchangeable.

"Sidereus Nuncius Magna," by Galileo Galilei, bound together with "Dissertatis cum Sidereus Nuncio" by Johannes Kepler, published in 1611. Learn more.

"Sidereus Nuncius Magna," by Galileo Galilei, bound together with "Dissertatis cum Sidereus Nuncio" by Johannes Kepler, published in 1611. Learn more.Considering how unavailable Sidereus Nuncius was for two centuries after its publication (it was not available in English until 1880), it has gone through many updates since 1880. Galileo's work was retranslated in 1960 as part of a more extensive work on scientific discovery. That translation dominated until 1989, when modern students deemed it not easily understood. The edition I reference, translated by professor Albert Van Helden in 1989, is still the prevailing version. Many advances have occurred since this translation, including an improved understanding of the telescope, the importance of the lenses and thus Galileo's comparative specialty as a lens-maker seen anew, and a better experience of the commercial trade of lenses, which gave some idea of how and why Galileo published with urgency, trying to get to press before anyone else with a telescope.

As Albert Van Helden states in the introduction:

What intrigued Galileo ... about the Moon was the irregularity of its surface as revealed by the new instrument. According to the then-prevailing geocentric cosmology of Aristotle, the heavens were perfect and unchanging, and heavenly bodies were perfectly smooth and spherical.

Galileo saw and noted moving and rising shadows on the moon, which he described simply as "lighter and darker shades" and "shadows of rising prominences." But his conclusion left no doubt that the moon was, in fact, earth-like.

It is thus known for certain and beyond doubt that they appear this way because of inequalities in the shapes of their parts and shadows moving diversely because of the varying illumination by the Sun.

"I felt about for my journal and laid there holding it, waiting for the moon to reappear," a night wakefulness captured by Patti Smith. Did Galileo feel similarly?

"I felt about for my journal and laid there holding it, waiting for the moon to reappear," a night wakefulness captured by Patti Smith. Did Galileo feel similarly?The great leap in consciousness that accompanies scientific advances (like Rachel Carson's 1962 study of pesticides or Anna Atkins's first photographic book) can expand our sense of being and render us quite helpless.

In 2020 we saw the oldest known universe through the eyes of the James Webb Telescope. In 2019 we learned how a black hole appears with more precision than we ever imagined. As new images stream into our feeds and minds and imagined reckoning of why we matter, what will we see next?

Galileo's drawing of the Pleiades, a cluster of stars about 450 light years away, formed 100 million years ago. Galileo first observed the Pleiades, although it is visible to the naked eye.

Galileo's drawing of the Pleiades, a cluster of stars about 450 light years away, formed 100 million years ago. Galileo first observed the Pleiades, although it is visible to the naked eye.One of my trusted guides to certainty in uncertain times, when wonder outpaces knowledge, is Alan Lightman, a professor of humanities and physics who seems to live within the gap of knowledge and wonder: "Nothing lasts. Nothing is indivisible. . . . Nothing is whole. Nothing is indestructible. Nothing is still." Read more in The Accidental Universe and Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine.

Galileo's understanding of our moon, stars, and sky handed humans life-changing knowledge. Yet, the sky and stars remain an illustrative metaphor that extends beyond the boundaries of science. A particular genius and generosity of humankind to imagine beyond perception.